I’ve written a sonnet, and I think it’s very good. Now I’d like to get paid for it so that I can quit my job and live off the revenue. Any suggestions?

I’ve written a sonnet, and I think it’s very good. Now I’d like to get paid for it so that I can quit my job and live off the revenue. Any suggestions?

Perhaps you’ve asked this question yourself: just substitute “iPhone app”, “blog”, “web site”, “Twitter mashup”, etc. for “sonnet”. You have a right to be proud that your app/blog/site is wonderful, but why won’t anyone pay you for it?

A pat on the head for young Billy

In school, when you did good work, you got rewarded, because school is a system designed to encourage you to do your best (at least, a good school is). In a job, when you do good work, you may get noticed and rewarded, depending on how much value your manager puts on continuing to treat you like a school student.

Outside of these artificially-constructed systems, however, nobody beyond friends and family gives a shit that you did something good — as Don Draper said on Mad Men “There is no system. The universe is indifferent.”

Don’t go past the fence!

Still, many brave or foolish people venture outside the school/employment sandbox every year, and the moment they go out the gate, they are hit with two shocks at once:

- Nobody wants to give them money.

- Nobody wants to give them praise.

If you’re going to have a chance of success, you recover from this shock, forget about chasing after praise (it’s mostly worthless), grit your teeth, and learn through trial and error how to provide enough value to other people that they’re willing to give you money in exchange.

That’s hard work — very hard work — and the heart of it is not simply promoting a product or service, but spending months and years developing real business relationships with people, and even more importantly, learning (and caring about) what those people — not you — want and need.

Shortcuts

Many people aren’t ready to face that kind of a shock, though, and at that point, they’re an easy mark for anything that promises an alternative to the hard (but necessary) work of actually dealing with people and caring about what they want. Every year, there seems to be at least one fad that promises a shortcut:

- You can run Google ads (or others) on your blog or web site, and Google will take care of finding and billing the customers, then will send you a monthly cheque.

- You can write a Twitter mashup or Facebook app, where Twitter or Facebook members will take care of the hard work of marketing for you, and you can then get enough visitors to cash in on those adds (or sell subscriptions through PayPal, etc.).

- You can post a video to YouTube, and get a share of ad revenue if it goes viral (insert buzzwords like “social media” where appropriate).

- You can write an iPhone or Android mobile app, and Apple or Google will find and bill your customers for you.

All of these promise money (however little they actually deliver), but more importantly, they promise that you can stay in a safe, non-Don-Draper-esque world like the one you remember from school or work: the world where you can get an A+ for doing a very good job on your essay, or a bonus for working extra hard on the ACME account. Effectively, Google, Apple, or some other organization becomes your teacher/parent/boss, dishing out rewards in the form of money and/or pageviews.

That’s a world most people understand; it’s a system where most people feel safe; but it’s no way to sell a sonnet.

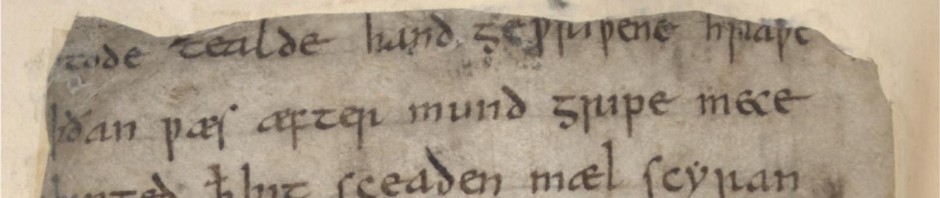

Shakespeare

To be honest, we don’t know if Shakespeare ever made money from his sonnets, but he did make a living from his plays … well, not so much from his plays, as from putting them on. It turns out that around the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th century, Londoners sometimes wanted to get out of the house and do something, but you can go to only so many bear-baitings and Morris dances before a certain ennui sets in.

Shakespeare didn’t just sit in a lonely garret writing plays to for someone else to put on (the 1600 equivalent of writing mobile apps for the iTunes store): as an actor, as part-owner of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later King’s Men), and as an investor in the Globe Theatre, Shakespeare threw himself directly into the hard work of forming relationships and dealing with his customers. He made enough money to go back to his home town and buy the second-largest house — a mansion, really — and lord it over everyone he grew up with.

After all that work, perhaps he wrote his sonnets just for fun.

(This post was inspired partly by my life partner, Bonnie Robinson, and the long hours she’s putting into Sweet Tarts Takeaway.)

I think this message is rather offensive to those of us who work for someone else for a living, though admittedly it isn’t addressed to us. But for the record, I do indeed expect and get praise, retention, bonuses, merit raises, and/or promotion when I do something good, and the opposite things if I do something bad. I don’t think you ought to call the way most people still live their lives an artificial sandbox; it trivializes the effort made and the very real and valuable work that gets done.

Good point, John — thanks for the feedback, and apologies for any offense. Employment is a carefully-designed, highly artificial system, but so is representational democracy, so that’s not automatically a bad thing.

I respect that not everyone will agree, but I believe it’s better not to take any employer’s praise, promotion, or financial incentives seriously — it’s far better to take pride in your work exclusively because you know it’s good. When that happens, you own your job, no matter who is signing the paycheques.

Well, I don’t take them too seriously in a psychological sense, but true approval comes not only from self-approval, but from peer repute.

I think we’ve arrived at a consensus, John. While I don’t think much of praise or incentives, sincere peer repute, honestly earned, is pure gold.

I accidentally saved before I was done. “But,” I was going to say, “the other things are of great value too, when there are children and grandchildren to feed.”

yo motherfucker this is the dumbest thing ive ever heard